Scribal traditions of "ancient" Hebrew scrolls

In 2006, I saw the dead sea scrolls in San Diego. The experience changed my life. I realized I knew nothing about ancient Judea, and decided to immerse myself in it. I studied biblical Hebrew and began a collection of Hebrew scrolls.

a pile of Torah scrolls

Each scroll is between 100 to 600 years old, and is a fragment of the Torah. These scrolls were used by synagogues throughout Southern Europe, Africa, and the Middle East. As we’ll see in a bit, each region has subtly different scribal traditions. But they all take their Torah very seriously.

The first thing that strikes me about a scroll is its color. Scrolls are made from animal skin, and the color is determined by the type of animal and method of curing the skin. The methods and animals used depend on the local resources, so color gives us a clue about where the scroll originally came from. For example, scrolls with a deep red color usually come from North Africa. As the scroll ages, the color may either fade or deepen slightly, but remains largely the same. The final parchment is called either gevil or klaf depending on the quality and preparation method.

The four scrolls below show the range of colors scrolls come in:

4 Torah scrolls side by side with different ages

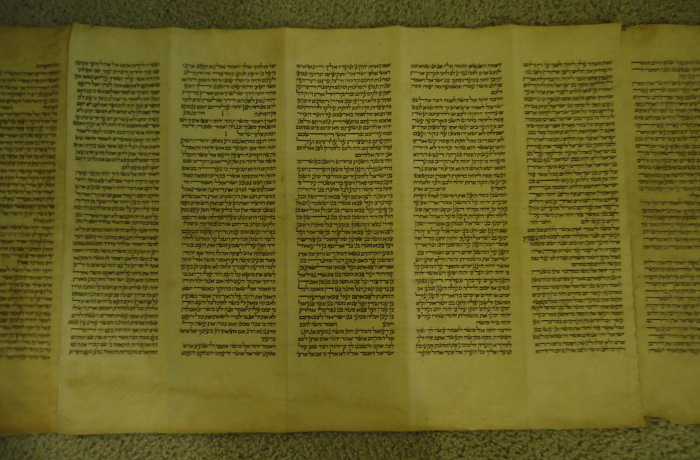

My largest scroll is about 60 feet long. Here I have it partially stretched out on the couch in my living room:

Torah scroll stretched out on couch

The scroll is about 300 years old, and contains most of Exodus, Leviticus, and Numbers. A complete Torah scroll would also have Genesis and Deuteronomy and be around 150 feet long. Sadly, this scroll has been damaged throughout its long life, and the damaged sections were removed.

As you can imagine, many hides were needed to make these large scrolls. These hides get sewn together to form the full scroll. You can easily see the stitching on the back of the scroll:

back of a Torah scroll

Also notice how rough that skin is! The scribes (for obvious reasons) chose to use the nice side of the skin to write on.

Here is a front end, rotated view of the same seam above. Some columns of text are separated at these seems, but some columns are not.

front of Torah seam

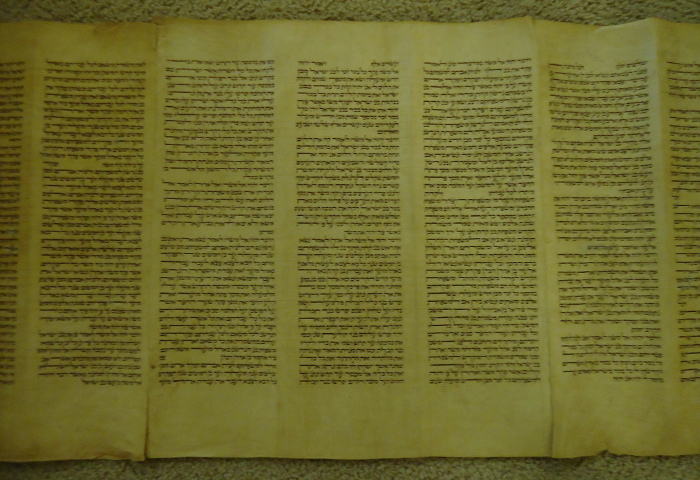

Animal hides come in many sizes. The hide in this image is pretty large and holds five columns of text:

5 panels of parchment

But this hide is smaller and holds only three columns:

3 panels of parchment

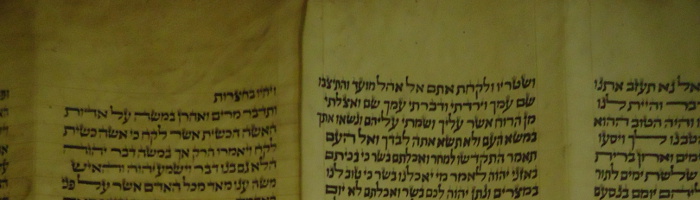

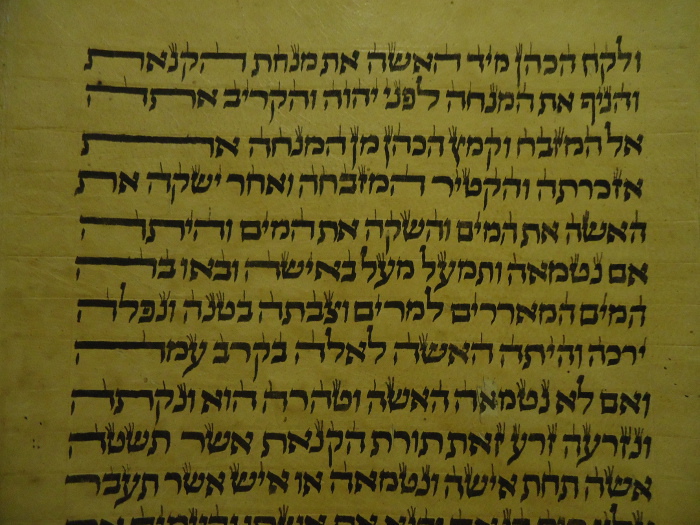

The coolest part of these scrolls is their calligraphy. Here’s a zoomed in look on one of the columns of text above:

zoomed in Hebrew Torah scroll

There’s a lot to notice in this picture:

The detail is amazing. Many characters have small strokes decorating them. These strokes are called tagin (or crowns in English). A bit farther down the page we’ll see different ways other scribal traditions decorate these characters. Because of this detail in every letter, a scribe (or sopher) might spend the whole day writing without finishing a single piece of parchment. The average sopher takes between nine months to a year to complete a Torah scroll.

There are faint indentations in the parchment that the sopher used to ensure he was writing straight. We learned to write straight in grade school by writing our letters on top of lines on paper. But in biblical Hebrew, the sopher writes their letters below the line!

Hebrew is read and written right to left (backwards from English). To keep the left margin crisp, the letters on the left can be stretched to fill space. This effect is used in different amounts throughout the text. The stretching is more noticeable in this next section:

Hebrew stretched letters in Torah scroll

And sometimes the sopher goes crazy and stretches all the things:

scribe stretched all the letters on this line of a Hebrew Torah

If you look at the pictures above carefully, you can see that only certain letters get stretched: ת ד ח ה ר ל. These letters look nice when stretched because they have a single horizontal stroke.

The next picture shows a fairly rare example of stretching the letter ש. It looks much less elegant than the other stretched letters:

stretching the shem letter in a Hebrew Torah scroll

Usually these stretched characters are considered mistakes. An experienced sopher evenly spaces the letters to fill the line exactly. But a novice sopher can’t predict their space usage as well. When they hit the end of the line and realize they can’t fit another full word, they’ll add one of these stretched characters to fill the space.

In certain sections, however, stretched lettering is expected. It is one of the signs of poetic text in the Torah. For example, in the following picture, the sopher intentionally stretched each line, even when they didn’t have to:

closeup of Torah scroll with cool calligraphy

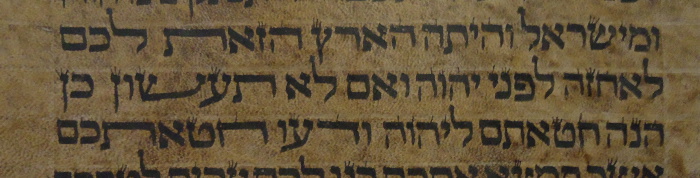

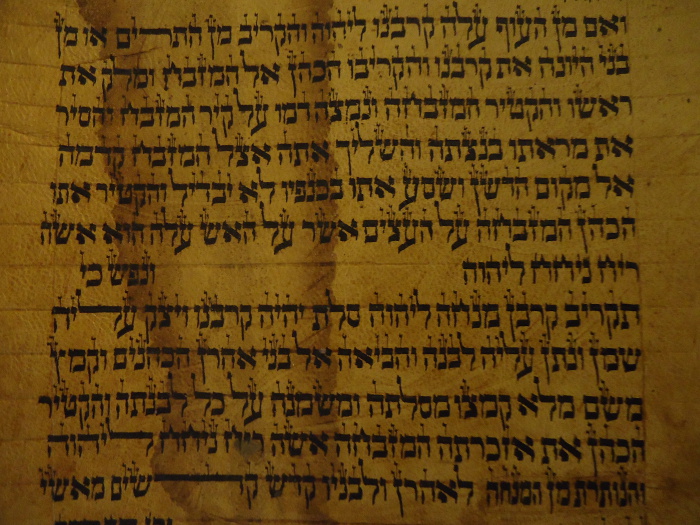

Keeping the left margin justified isn’t just about looks. The Torah is divided into thematic sections called parashot. There are two types of breaks separating parashot. The petuha (open) is a jagged edge, much like we end paragraphs in English. The setumah (closed) break is a long space in the middle of the line. The picture below shows both types of breaks:

Torah scroll containing a petuha and setumah parashah break

A sopher takes these parashot divisions very seriously. If the sopher accidentally adds or removes parashot from the text, the entire scroll becomes non-kosher and cannot be used. A mistake like this would typically be fixed by removing the offending piece of parchment from the scroll, rewriting it, and adding the corrected version back in. (We’ll see some pictures of less serious mistakes at the bottom of this page.)

The vast majority of of the Torah is formatted as simple blocks of text. But certain sections must be formatted in special ways. This is a visual cue that the text is more poetic.

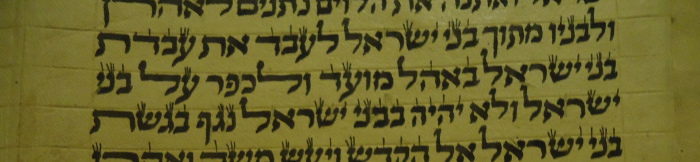

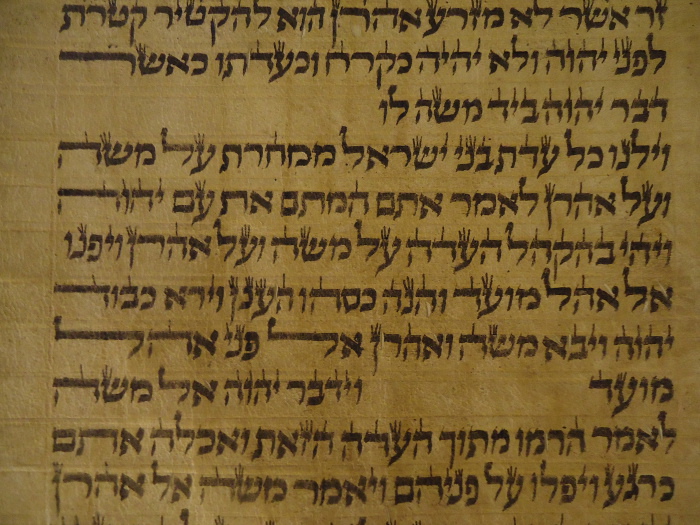

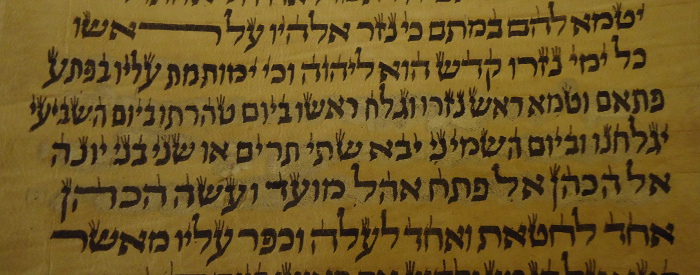

The passage below is of Numbers 10:35-36. Here we see an example of the inverted nun character being used to highlight some text. This is the only section of the Torah where this formatting appears (although it also appears seven times in the book of psalms). The inverted nun characters are set all by themselves, and surround a command about the Ark of the Covenant:

Moses gives a command about the ark of the covenant in fancy Hebrew script; inverted nun character

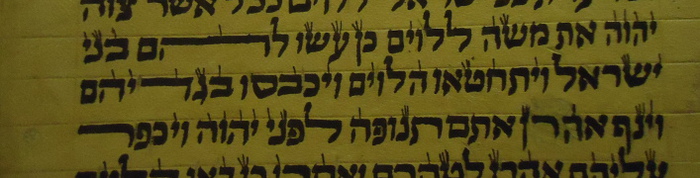

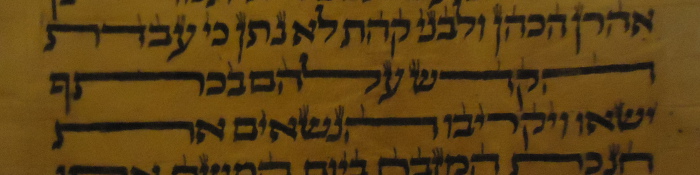

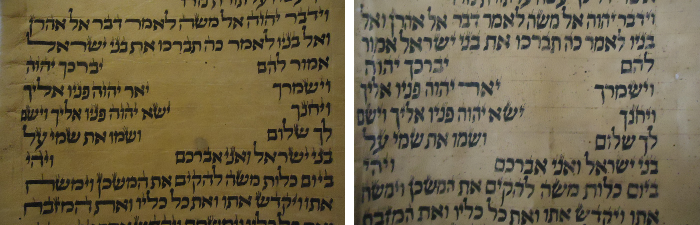

It’s really cool when two different scrolls have sections that overlap. We can compare them side-by-side to watch the development of different scribal traditions. The image below shows two versions of Numbers 6:22-27.

The lord bless you and keep you rendered in a Hebrew Torah in fancy Hebrew script

The writing is almost identical in both versions, with one exception. On the first line with special formatting, the left scroll has two words in the right column: אמור להם, but the right scroll only has the world אמור) להם is the last word on the previous line). When the sopher is copying a scroll, he does his best to preserve the formatting in these special sections. But due to the vast Jewish diaspora, small mistakes like this get made and propagate. Eventually they form entirely new scribal traditions. (Note that if a single letter is missing from a Torah, then the Torah is not kosher and is considered unfit for use. These scribal differences are purely stylistic.)

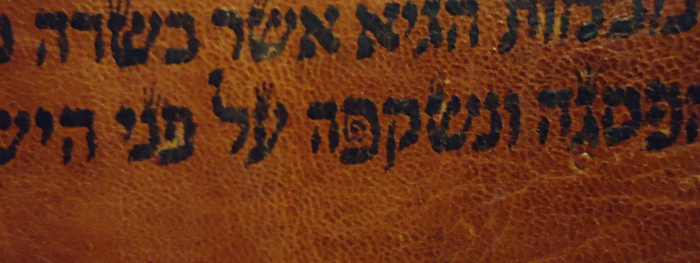

Many individual characters and words also receive special formatting throughout the text. Both images below come from the same piece of parchment (in Genesis 23) and were created by the same sopher. The image on the left shows the letter פ in its standard form, and the image on the right shows it in a modified form.

a whirled pe in the Hebrew Torah side by side with a normal pe

The meaning of these special characters is not fully known, and every scribal tradition exhibits some variation in what letters get these extra decorations. In the scroll above, the whirled פ appears only once. But some scrolls exhibit the special character dozens of times. Here is another example where you can see a whirled פ a few letters to the right of its normal version:

a whirled pe and normal pe in the Hebrew Torah in the same sentence

Another special marker is when dots are placed over the Hebrew letters. The picture below comes from the story when Esau is reconciling with Jacob in Genesis 33. Normally, the dotted word would mean that Esau kissed Jacob in reconciliation; but tradition states that these dots indicate that Esau was being incincere. Some rabbis say that this word, when dotted, could be more accurately translated as Esau “bit” Jacob.

dots above words on the Hebrew Torah

Next, let’s take a look at God’s name written in many different styles. In Hebrew, God’s name is written יהוה. Christians often pronounce God’s name as Yahweh or Jehovah. Jews, however, never say God’s name. Instead, they say the word adonai, which means “lord.” In English old testaments, anytime you see the word Lord rendered in small caps, the Hebrew is actually God’s name. When writing in English, Jews will usually write God’s name as YHWH. Removing the vowels is a reminder to not say the name out loud.

Below are nine selected images of YHWH. Each comes from a different scroll and illustrates the decorations added by a different scribal tradition. A few are starting to fade from age, but they were the best examples I could find in the same style. The simplest letters are in the top left, and the most intricate in the bottom right. In the same scroll, YHWH is always written in the same style.

yahweh, jehova, the name of god, in many different Hebrew scripts

The next image shows the word YHWH at the end of the line. The ה letters get stretched just like in any other word. When I first saw this I was surprised a sopher would stretch the name of God like this—the name of God is taken very seriously and must be handled according to special rules. I can just imagine rabbis 300 years ago getting into heated debates about whether or not this was kosher!

stretched yahweh in Hebrew Torah scroll

There is another oddity in the image above. The letter yod (the small, apostrophe looking letter at the beginning of YHWH) appears in each line. But it is written differently in the last line. Here, it is given two tagin, but everywhere else it only has one. Usually, the sopher consistently applies the same styling throughout the scroll. Changes like this typically indicate the sopher is trying to emphasize some aspect of the text. Exactly what the changes mean, however, would depend on the specific scribal tradition.

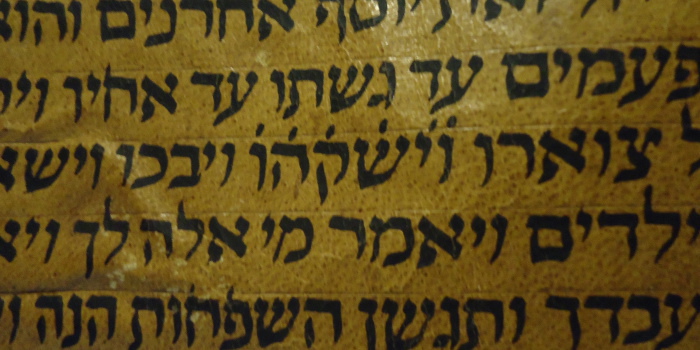

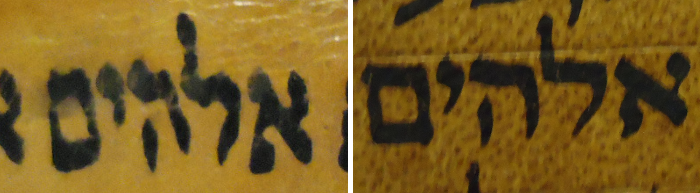

The more general word for god in Hebrew is אלוהים, pronounced elohim. This word can refer to either YHWH or a non-Jewish god. Here it is below in two separate scrolls:

elohim, god, in Hebrew

Many Christians, when they first learn Hebrew, get confused by the word elohim. The ending im on Hebrew words is used to make a word plural, much like the ending s in English. (For example, the plural of sopher is sophrim.) Christians sometimes claim that because the Hebrew word for god looks plural, ancient Jews must have believed in the Christian doctrine of the trinity. But this is very wrong, and rather offensive to Jews.

Tradition has that Moses is the sole author of the Torah, and that Jewish sophrim have given us perfect copies of Moses’ original manuscripts. Most modern scholars, however, believe in the documentary hypothesis, which challenges this tradition. The hypothesis claims that two different writers wrote the Torah. One writer always referenced God as YHWH, whereas the other always referenced God as elohim. The main evidence for the documentary hypothesis is that some stories in the Torah are repeated twice with slightly different details; in one version God is always called YHWH, whereas in the other God is always called elohim. The documentary hypothesis suggests that some later editor merged two sources together, but didn’t feel comfortable editing out the discrepancies, so left them exactly as they were. Orthodox Jews reject the documentary hypothesis, but some strains of Judaism and most Christian denominations are willing to consider that the hypothesis might be true. This controversy is a very important distinction between different Jewish sects, but most Christians aren’t even aware of the controversy in their holy book.

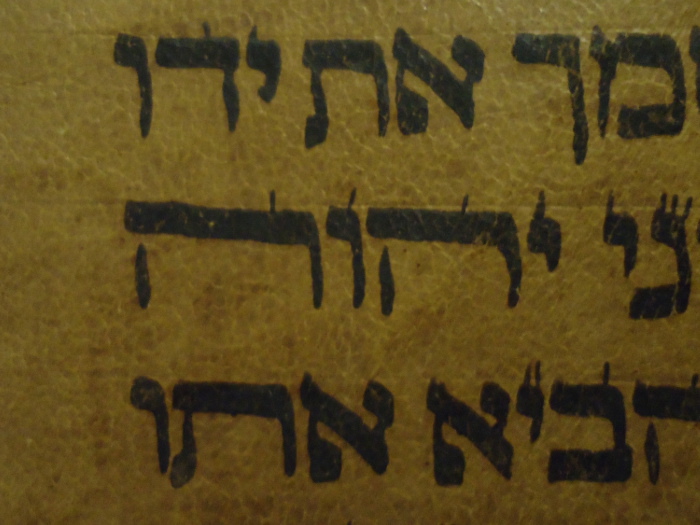

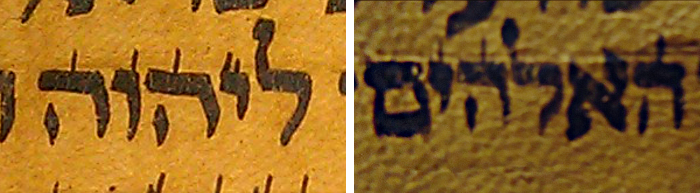

The next two pictures show common gramatical modifications of the words YHWH and elohim: they have letters attached to them in the front. The word YHWH below has a ל in front. This signifies that something is being done to YHWH or for YHWH. The word elohim has a ה in front. This signifies that we’re talking about the God, not just a god. In Hebrew, prepositions like “to,” “for,” and “the” are not separate words. They’re just letters that get attached to the words they modify.

lamed on yhwh adonai plus a he on elohium

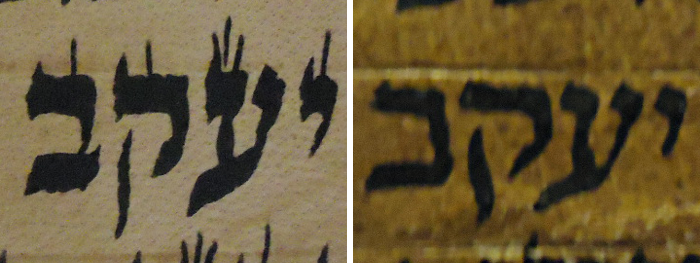

Names are very important in Hebrew. Most names are actually phrases. The name Jacob, for example, means “heel puller.” Jacob earned his name because he was pulling the heel of his twin brother Esau when they were born in Genesis 25:26. Below are two different versions of the word Jacob:

the name jacob written in fancy Hebrew script; genesis 25:26

But names often change in the book of Genesis. In fact, Jacob’s name is changed to Israel in two separate locations: first in Genesis 32 after Jacob wrestles with “a man”; then again in Genesis 35 after Jacob builds an alter to elohim. (This is one of the stories cited as evidence for the documentary hypothesis.) The name Israel is appropriate because it literally means “persevered with God.” The el at the end of Israel is a shortened form of elohim and is another Hebrew word for god.

Here is the name Israel in two different scripts:

Israel in Torah script Hebrew

Another important Hebrew name is ישוע. In Hebrew, this name is pronounced yeshua, but Christians commonly pronounce it Jesus! The name literally translates as “salvation.” That’s why the angel in Matthew 1:21 and Luke 1:31 gives Jesus this name. My scrolls are only of the old testament, so I don’t have any examples to show of Jesus’ name!

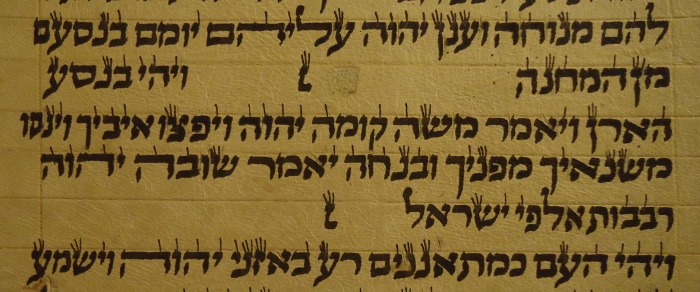

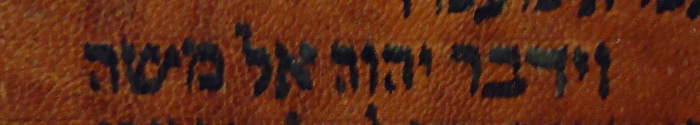

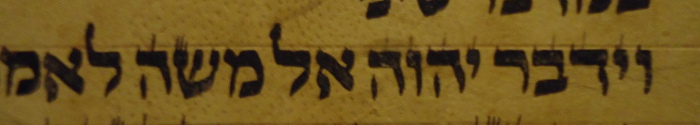

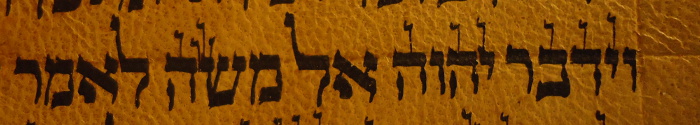

To wrap up the discussion of scribal writing styles, let’s take a look at the most common phrase in the Torah: ודבר יהוה אל משה. This translates to “and the Lord said to Moses.” Here is is rendered in three different styles:

vaydaber adonai lmosheh

vaydaber adonai lmosheh

vaydaber adonai lmosheh

Now let’s move on to what happens when the sophrim make mistakes.

Copying all of these intricate characters was exhausting work! And hard! So mistakes are bound to happen. But if even a single letter is wrong anywhere in the scroll, the entire scroll is considered unusable. The rules are incredibly strict, and this is why Orthodox Jews reject the documentary hypothesis. To them, it is simply inconceivable to use a version of the Torah that was combined from multiple sources.

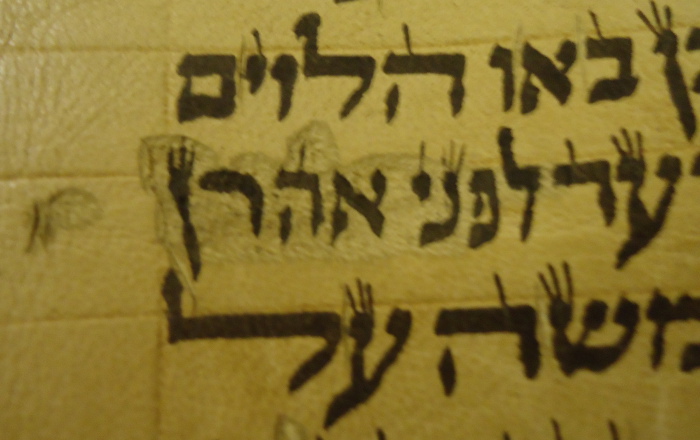

The most common way to correct a mistake is to scratch off the outer layer of the parchment, removing the ink. In the picture below, the sopher has written the name Aaron (אהרן) over the scratched off parchment:

scribe mistake in Hebrew Torah scroll

The next picture shows the end of a line. Because of the mistake, however, the sopher must write several characters in the margin of the text, ruining the nice sharp edge they created with the stretched characters. Writing that enters the margins like this is not kosher.

scribe mistake in Hebrew Torah scroll

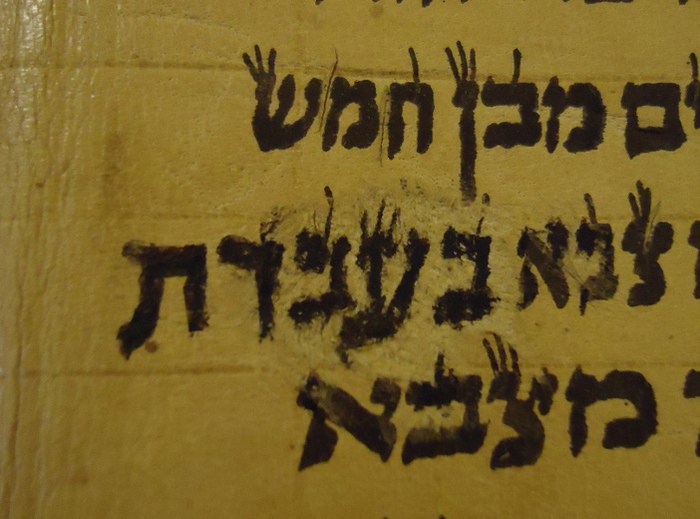

Sometimes a sopher doesn’t realize they’ve made a mistake until several lines later. In the picture below, the sopher has had to scratch off and replace three and a half lines:

scribe makes a big mistake and scratches off several lines in a Torah scroll

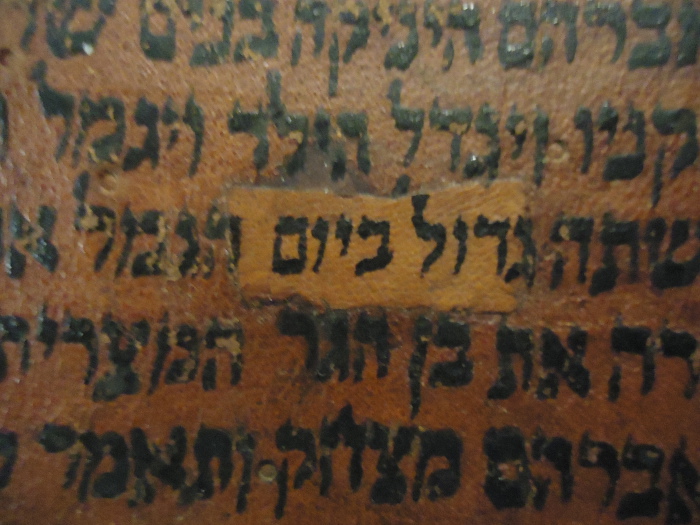

Scratching the parchment makes it thinner and weaker. Occasionally the parchment is already very thin, and scratching would tear through to the other side. In this case, the sopher can take a thin piece of blank parchment and attach it to the surface. In the following picture, you can see that the attached parchment has a different color and texture.

parchment mistake added ontop Torah scroll

The next picture shows a rather curious instance of this technique. The new parchment is placed so as to cover only parts of words on multiple lines. I can’t imagine how a sopher would make a mistake that would best be fixed in this manner. So my guess is that this patch was applied some time later, by a different sopher to repair some damage that had occurred to the scroll while it was in use.

parchment of repair added to the top of a Torah scroll

Our last example of correcting mistakes is the most rare. Below, the sopher completely forgot a word when copying the scroll, and added it in superscript above the standard text:

superscript mistake fixing in Toral scroll

If we zoom in, you can see that the superscript word is slightly more faded than the surrounding text. This might be because the word was discovered to be missing a long time (days or weeks) after the original text was written, so a different batch of ink was used to write the word.

superscript mistake fixing in Toral scroll

Since these scrolls are several hundred years old, they’ve had plenty of time to accumulate damage. When stored improperly, the parchment can tear in some places and bunch up in others:

parchment Torah scroll damage

One of the worst things that can happen to a scroll is water. It damages the parchment and makes the ink run. If this happens, the scroll is ruined permanently.

water damage on a torah scroll

you should learn Hebrew!

If you’ve read this far and enjoyed it, then you should learn biblical Hebrew. It’s a lot of fun! You can start right now at any of these great sites:

http://foundationstone.com.au - geared for the Jewish reader, covers both biblical and modern Hebrew

http://hebrew4christians.com - very good site because it also explains lots of Jewish customs that may be unfamiliar to you; this should probably be more accurately named “hebrew4gentiles”

http://www.ulpan.net - the focus is on modern Hebrew, but the basics are the same

http://www.101languages.net/hebrew - also modern Hebrew

When you’re ready to get serious, you’ll need to get some books. The books that helped me the most were:

These books all have lots of exercises and make self study pretty simple. The Biblical Hebrew Workbook is for absolute beginners. Within the first few sessions you’re translating actual bible verses and learning the nuances that get lost in the process. I spent two days a week with this book, two hours at each session. It took about four months to finish.

The other two books start right where the workbook stops. They walk you through many important passages and even entire books of the old testament. After finishing these books, I felt comfortable enough to start reading the old testament by myself. Of course I was still very slow and was constantly looking things up in the dictionary!

For me, learning the vocabulary was the hardest part. I used a great free piece of software called FoundationStone to help. The program remembers which words you struggle with and quizes you on them more frequently.

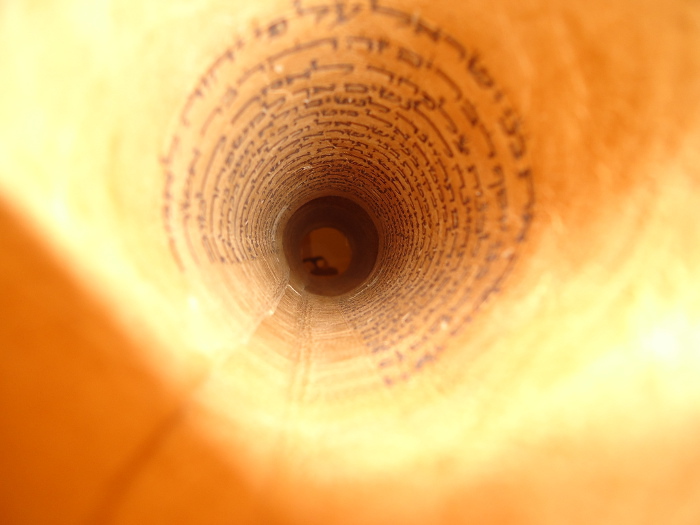

Finally, let’s end with my favorite picture of them all. Here we’re looking down through a rolled up Torah scroll at one of my sandals.

torah sandals james bond