Comparing AVL Trees in C++ and Haskell

This post compares the runtimes of AVL tree operations in C++ vs Haskell. In particular, we insert 713,000 strings from a file into an AVL Tree. This is a \(O(n \log n)\) operation. But we want to investigate what the constant factor looks like in different situations.

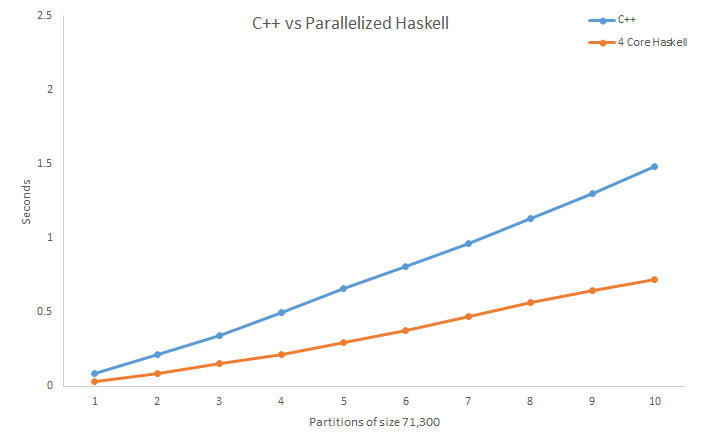

Experimental setup: All the code for these tests is available in the github repository. The C++ AVL tree was created in a data structures course that I took recently and the Haskell AVL tree is from the Haskell library Data.Tree.AVL. Additionally, the Haskell code stores the strings as ByteStrings because they are much more efficient than the notoriously slow String. To see how the runtime is affected by files of different sizes, the file was first partitioned into 10 segments. The first segment has 71,300 words, the second 71,300 * 2 words, and so on. Both the C++ and Haskell programs were compiled with the -O2 flag for optimization. The test on each segment is the average runtime of three separate runs.

Here’s the results:

C++vHaskell

C++ is a bit faster than Haskell on the last partition for this test.

I guess this is because Haskell operates on immutable data. Every time a new element is to be inserted into the Haskell AVL tree, new parent nodes must be created because the old parent nodes cannot be changed. This creates quite a bit of overhead. C++ on the other hand, does have mutable data and can simply change the node that a parent node is pointing to. This is faster than making a whole new copy like the Haskell code does.

Is there an easy way to speed up our Haskell code?

There is a Haskell library called parallel that makes parallel computations really convenient. We’ll try to speed up our program with this library.

You might think that it is unfair to compare multithreaded Haskell against C++ that is not multithreaded. And you’re absolutely right! But let’s be honest, manually working with pthreads in C++ is quite the headache, but parallism in Haskell is super easy.

Before we look at the results, let’s look at the parallelized code. What we do is create four trees each with a portion of the set of strings. Then, we call par on the trees so that the code is parallelized. Afterwards, we union the trees to make them a single tree. Finally, we call deepseq so that the code is evaluated.

{-# LANGUAGE TemplateHaskell #-}

import Control.DeepSeq.TH

import Control.Concurrent

import Data.Tree.AVL as A

import Data.COrdering

import System.CPUTime

import qualified Data.ByteString.Char8 as B

import Control.DeepSeq

import Data.List.Split

import System.Environment

import Control.Parallel

$(deriveNFData ''AVL)

-- Inserts elements from list into AVL tree

load :: AVL B.ByteString -> [B.ByteString] -> AVL B.ByteString

load t [] = t

load t (x:xs) = A.push (fstCC x) x (load t xs)

main = do

args <- getArgs

contents <- fmap B.lines $ B.readFile $ args !! 0

let l = splitEvery (length contents `div` 4) contents

deepseq contents $ deepseq l $ return ()

start <- getCPUTime

-- Loading the tree with the subpartitions

let t1 = load empty $ l !! 0

let t2 = load empty $ l !! 1

let t3 = load empty $ l !! 2

let t4 = load empty $ l !! 3

let p = par t1 $ par t2 $ par t3 t4

-- Calling union to combine the trees

let b = union fstCC t1 t2

let t = union fstCC t3 t4

let bt = union fstCC b t

let bt' = par b $ par t bt

deepseq p $ deepseq bt' $ return ()

end <- getCPUTime

n <- getNumCapabilities

let diff = ((fromIntegral (end-start)) / (10^12) / fromIntegral n)

putStrLn $ show diffGreat, so now that the Haskell code has been parallelized, we can compile and run the program again to see the difference. To compile for parallelism, we must use some special flags.

ghc –O2 filename -rtsopts –threadedAnd to run the program (-N4 refers to the number of cores).

./filename +RTS –N4

C++vHaskell4

Haskell now gets better runtimes than C++.

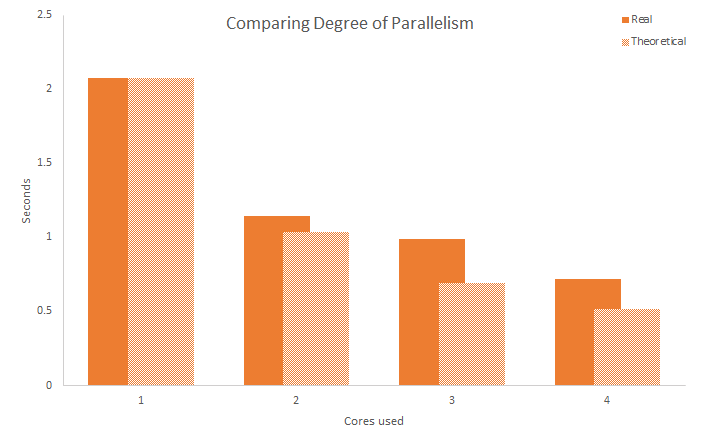

Now that we know Haskell is capable of increasing its speeds through parallelism, it would be interesting to see how the runtime is affected by the degree of parallelism.

According to Amdahl’s law, a program that is 100% parallelized will see a proportional speed up based on the number of threads of execution. For example, if a program that is 100% parallelized takes 2 seconds to run on 1 thread, then it should take 1 second to run using 2 threads. The code used for our test, however, is not 100% parallelized since there a union operation performed at the end to combine the trees created by the separate threads. The union of the trees is a \(O(n)\) operation while the insertion of the strings into the AVL tree is a \(O\left(\frac{n \log n }{p}\right)\) operation, where \(p\) is the number of threads. Therefore, the runtime for our test should be

\[O\left(\frac{n\log{n}}{p} + n\right)\]

Here is a graph showing the runtime of the operation on the largest set (713,000 strings) across increasing levels of parallelism.

HaskellParallelization

Taking a look at the results, we can see that the improvement in runtime does not fit the 100% parallelized theoretical model, but does follow it to some extent. Rather than the 2 core runtime being 50% of the 1 core runtime, the 2 core runtime is 56% of the 1 core runtime, with decreasing efficiency as the number of cores increases. Though, it is clear that there are significant improvements in speed through the use of more processor cores and that parallelism is an easy way to get better runtime speeds with little effort.